Considerations in Wording

Words are extremely powerful and we react instinctively to their underlying meanings. Knowing how to word questions in a neutral yet effective is therefore an art to which many books have been dedicated.

There are a number of common errors in question wording that should be avoided.

1. Loaded words, or words that stir up immediate positive or negative feelings. When loaded words are used, respondents react more to the word itself than to the issue at hand. Not surprisingly, the estimated speed of the car was much higher for group A than for group B in the following experiment:

Two groups of people (A & B) were shown a short film about a car crash. Group A was asked "How fast was car X going when it smashed into car Y?" while Group B was asked "How fast was car X going when it contacted car Y?"

Many similar experiments have shown the power of words to introduce such a bias.

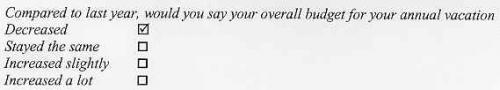

2. Loaded response categories, or providing a range of responses that will skew the answers in one direction or another. In the following example:

You have biased the answers towards "increase" since there are two categories that address degrees of increase, compared to only one category for a potential decrease. You need to balance this scale by changing "decreased" to "decreased a lot" and "decreased slightly".

3. Leading questions, or questions that suggest socially acceptable answers or in some way intimate the viewpoint held by the researcher, can lead respondents to answer in a way that does not reflect their true feelings or thoughts. For instance, in a survey about all-inclusive holidays, the question "How much time did you devote to your child(ren) during your vacation?" will lead people to overestimate the time spent, since to answer "I did not spend any time or little time" would almost be like saying they were not devoted to their offspring. It is very important to find words that do not make assumptions about the respondents or are neutral in nature.

4. Double-barrelled questions are questions that require more than one answer, and therefore should be broken into at least two questions. For instance, "How would you rate the quality of service provided by our restaurant and room-service staff?" does not allow you determine which is being rated, the restaurant staff or the room-service staff, nor whether either or both were used. It would be far better to have separate questions dealing with these issues.

5. Vague words or phrases can pose a special problem, since sometimes you want to be deliberately vague because you are exploring an issue and don’t want to pre-determine or influence the answers being considered. However, there are some common rules that you can follow:

- Always specify what "you" refers to as in "you, personally" or "you and your family"

- Always give a precise time frame: "How often in the last two months…", "In 1998…(not "last year")", "July and August (instead of "during the summer")"

- Stay away from terms such as "rarely" or "often", if you can since they can be interpreted in many different ways. Use terms such as "once a month", "several times a week" that are more specific.

- When probing for specific quantitative details, don’t tax the respondent’s memory unreasonably. "How many ads for different destinations did you see in the last month?" is an almost impossible question to answer even though the time frame is ‘only’ a month. Since most of us are inundated with advertising messages of all types, you cannot expect a meaningful answer. It would be better to probe for destinations that have stood out or ads that have marked the respondent in some way.

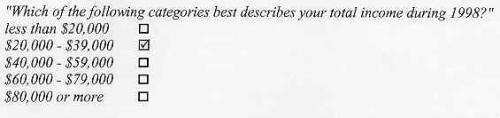

6. Offensive or threatening questions, even if inadvertent, can lead to a dishonest answer or refusal. This applies even to a blunt question about income as in "What is your income?_______" It is better to rephrase such a question by providing broad categories, for example

It is rare that you really need very precise income information, and for most types of research this type of broad category would be sufficient. This is part of the considerations around "nice to know" information versus information needed to specifically answer the research problem.

7. Jargon, acronyms and technical language should be avoided in favour of more conversational language and the use of terms that are readily understood by everyone. It should not be taken for granted, for instance, that everyone would be familiar with even relatively common terms such as "baby boomer", "GTA" or "brand image", and it is far better to spell them out: "those born after the Second World War but before 1960", "the cities in the Oshawa-Hamilton corridor" and "the image reflected by the name or symbol used to identify a service provided", even if this may appear to be cumbersome.

Pamela Narins, the Market Research Manager for SPSS, has prepared some excellent pointers on how to "write more effective survey questions". Be sure to check them out!