How companies should respond to U.S.-China tensions and global supply chain disruption

Felix Arndt, University of Guelph; Abby Jingzi Zhou, University of Nottingham; Christiaan Röell, University of Sheffield; Steven Shijin Zhou, University of Nottingham, and Xiaomeng Liu, University of Nottingham

Ongoing tensions between the United States and China have affected many companies around the world, including those in Canada.

Canada’s relationship to China has suffered due to the legal saga involving Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou. The COVID-19 pandemic has also made it very clear that a reliance on Chinese suppliers — for companies everywhere — can have disastrous consequences when these supply chains are interrupted.

In this challenging and uncertain time, many companies are trying to reorganize their supply chains and reduce dependencies that are vulnerable to political tensions and rising costs.

While the pandemic has already compelled many companies to become more agile — for example by increasing their number of suppliers — business leaders must now start thinking about the long-term implications of increased uncertainty in the markets since volatility is likely here to stay.

Our ongoing research suggests two factors are most important when making decisions on how to respond to the U.S.-China trade war: location and supply chain dependence, and technology.

Ending dependence on two fronts

The first factor deals with how much dependence companies have on Chinese suppliers and customers. China offers a uniquely complete combination of supply chains and a growing middle class that fuels high demand for almost any good.

According to a United Nations report, China is home to almost every industry and its companies offer almost the full range of products and services in each of these industries.

The second factor is technology dependence. In some industries, blazing a trail on the technology frontier is key to success. North America is still the leading region for many of these technologies (including biotechnology, cultured meat and artificial intelligence) and it’s increasingly concerned about its intellectual property falling into Chinese hands.

Recent restrictions on Chinese researchers in Canadian universities are one example of protectionist actions spurred by these concerns.

In the future, companies that deal with North American technologies in cutting-edge areas will probably have to avoid delivering to China or using this technology in collaborations with any Chinese companies.

Low vs. high Chinese dependence

Companies with different degrees of dependence on Chinese supply chains and North American technologies are likely to behave very differently. We walk through the four scenarios.

Companies with low reliance on both North American technology and Chinese supply chains tend to relocate their manufacturing facilities to a third, low-wage country, such as Vietnam and India, because it’s easy to find alternative production sites and to access technology.

Samsung’s display business, offering digital signage and hospitality displays, is an example. Samsung’s reliance on Chinese supply chains is low because it owns a relatively complete supply chain ranging from upstream activities (inputs to products, such as chip design) to downstream activities (outputs such as products, like smartphones).

In short, Samsung designs, manufactures and markets its own products. The reliance on North American technology is also low because the technology required to produce display devices is not limited to North America. As a result, Samsung has shifted its manufacturing of IT and mobile displays from China to India, avoiding tariffs and higher wages in China.

But companies with high dependence on Chinese supply chains could have a hard time leaving China. Take Google’s Pixel phone as an example.

In 2019, Google decided to relocate the manufacturing of the Pixel phone from China to Bac Ninh in northern Vietnam to avoid tariffs into the U.S., an important market for its phones. Two years later, Google reversed the decision and started producing the new smartphone in China due to supply chain problems amid increasing uncertainty from pandemic-related restrictions.

Relocations to North America

Companies with a high reliance on North American technology and a relatively low reliance on Chinese supply chains, on the other hand, are likely to relocate manufacturing to North America.

For instance, TSMC, one of the world’s leading semiconductor foundries, uses substantial American technologies and equipment, including advanced equipment for ultraviolet lithography. Therefore, the Taiwanese company decided to build a new advanced chip factory in Arizona, a decision closely connected to its dependence on both U.S. technology and customers.

Companies with high reliance on both North American technology and the Chinese supply chain face the biggest challenges. They have no choice but to keep operating in both countries while navigating political risks and market turbulence.

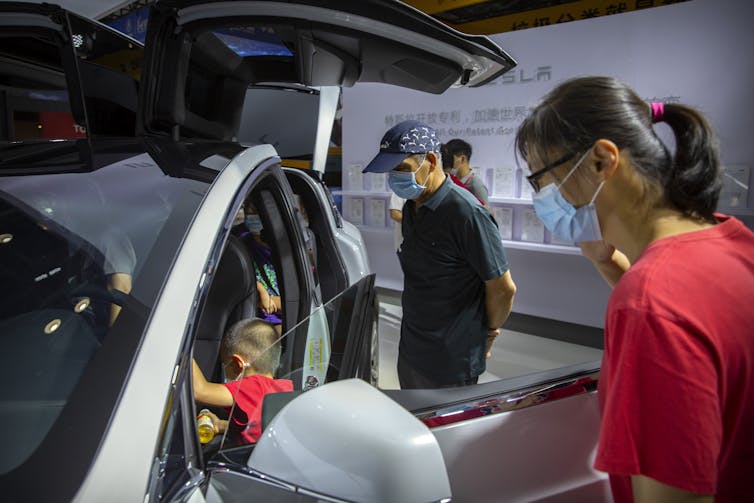

Tesla is a prime example. While dependent on its research and development in the U.S. to enhance its leading technology position, China’s supply chain benefits Tesla with manufacturing speed, cost and proximity to the Chinese market. That leaves companies like Tesla with no choice but to navigate political tensions and stay present in both markets.

As a result, Tesla has built and expanded a factory in Shanghai. Additionally, it has promised to conduct more research and development activities in China and to recruit local talent for local design.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been another wake-up call for business leaders that should have prompted them to consider the importance of technological progress and supply chain security. While we don’t know how long the pandemic and its restrictions will endure, successful companies think ahead and build resilience and flexibility into their operations.![]()

Felix Arndt, John F. Wood Chair in Entrepreneurship, University of Guelph; Abby Jingzi Zhou, Associate Professor, International Business, University of Nottingham; Christiaan Röell, Lecturer in International Business, University of Sheffield; Steven Shijin Zhou, Associate Professor, International Business, University of Nottingham, and Xiaomeng Liu, PhD Student, International Business, University of Nottingham

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.