Malignant catarrhal fever in a bison cow

Margaret Stalker, Christiane Buschbeck

Animal Health Laboratory, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON (Stalker);

Markdale Veterinary Services, Markdale, ON (Buschbeck).

AHL Newsletter 2021;25(3):9.

A 15-year old bison cow that had calved 3 months previously was found dead with evidence of non-specific trauma including horn marks and subcutaneous hematomas. A postmortem examination revealed abomasal ulcers.

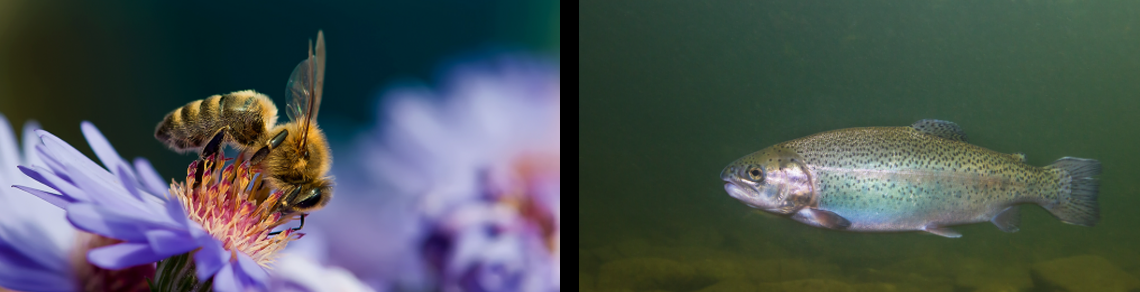

Histologic examination of tissues confirmed acute abomasitis, as well as chronic lymphoplasmacytic portal hepatitis (Fig. 1) and mild pulmonary perivascular lymphoplasmacytic cuffing with localized acute alveolitis (Fig. 2). Clostridia FA testing was negative. A herd history of previous cases prompted PCR testing for malignant catarrhal fever (MCF). PCR was positive at a low cycle threshold (Ct value 22.08), indicating the presence of ovine herpesvirus-2 (OHV-2) in high concentration in the sample of liver tissue tested.

There have been four Ontario bison herds with individual animals diagnosed with MCF over the last 10 years at the AHL. Bison are considered to be extremely susceptible to infection. The clinical presentation of disease in bison is variable, with an acute clinical disease being most common, as well as rarer subclinical forms (1, 2). The clinical history may be brief, <1-4 days, and mortality rates in bison herds can be high, particularly if animals are stressed or crowded. Affected animals may be found depressed and isolated from their herd mates, or more commonly found dead or dying. Clinical signs may be subtle and include oculonasal discharge, conjunctival hyphema, pyrexia, dysentery and hematuria/stranguria.

On postmortem, lesions include erosive rhinitis, stomatitis and esophagitis, ulcers in the forestomachs and abomasum, and a necrohemorrhagic typhlocolitis. Hemorrhagic cystitis is also a common finding in bison with MCF. Unlike cattle, generalized lymph node hyperplasia, while present, is not pronounced. Terminally ill bison may be attacked and wounded by herd mates, as in this case. On histology, vasculitis lesions are typically less florid than in cattle.

Previously, additional single cases of MCF have been diagnosed in bison on this premises over the past 4 years. Proximity to sheep, the carriers of OHV-2, is required for transmission. However, the virus can spread via aerosol over surprisingly long distances (up to 5 km), based on natural outbreaks (1). In this herd, the source of the virus may be a small ruminant farm located across the road.

The OAHN Small Ruminant Network has recently released a short update MCF in Bison https://www.oahn.ca/resources/managing-the-risk-of-malignant-catarrhal-fever-mcf-from-sheep-to-bison/

AHL

Figure 1. Lymphoplasmacytic portal hepatitis. H&E stain.

Figure 2. Mild pulmonary perivascular lymphoplasmacytic cuffing with localized acute alveolitis. H&E stain.

References

1. O’Toole D and Li H. The pathology of malignant catarrhal fever, with an emphasis on ovine herpesvirus 2. Vet Pathol 2014;51(2):437-52.

2. Schultheiss PC, et al. Malignant catarrhal fever in bison, acute and chronic cases. JVDI 1998;10:255-262.