Presumptive dermatosparaxis in a beef steer

Emily Brouwer, Emily zur Linden

Animal Health Laboratory, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON (Brouwer), Metzger Veterinary Services, Linwood, ON (zur Linden).

AHL Newsletter 2024;28(1):21.

In early December, a feedlot producer called the veterinarian to examine a 1300 lb. Holstein-Angus cross steer with a large lump on the right shoulder. It was noted at the time of examination that this mass was a large fluid-filled sac (seroma). Upon further examination, it was noted that the steer had excessive skin on the forehead, and loose folds of skin over the body (Fig. 1). Upon manipulation, the skin was noted to be excessively elastic and pulled away from the body and face easily. The veterinarian suspected bovine dermatosparaxis and took several skin biopsies of this steer and an age-matched control and submitted them to the Animal Health Laboratory for microscopic examination.

Figures 1. Affected steer with excessive loose folds of skin. A. Excessive loose skin on the forehead and right brisket region. B. Left side of the neck with highly folded skin and focus of erosion.

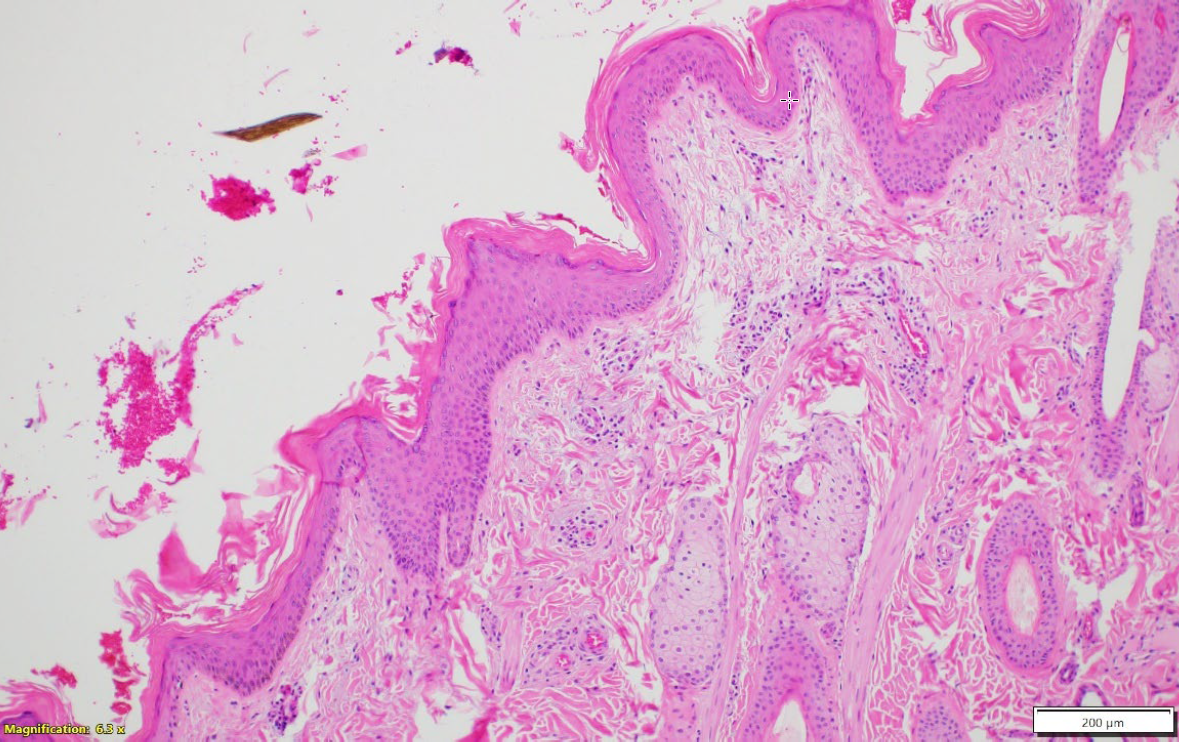

In all sections of skin, the epidermis is mildly hyperplastic, hyperkeratotic, and has a thickened basement membrane. There is a subtle increase in loose basophilic ground substance surrounding slightly thinner and haphazardly arranged superficial dermal collagen bundles and superficial dermal vessels. There are clustered eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells surrounding superficial dermal vessels (Fig. 2). Collagen bundles in the deep dermis are histologically unremarkable but are widely separated and surrounded by thinner bands of collagen. Deep dermal blood vessels often have thickened vascular walls, with occasional lamellar mural fibrosis.

Figure 2. Affected skin, Hematoxylin and Eosin stain, 10X. The epidermis is mildly hyperplastic, hyperkeratotic and has a thickened basement membrane. There is increased dermal ground substance and thin superficial dermal collagen bundles.

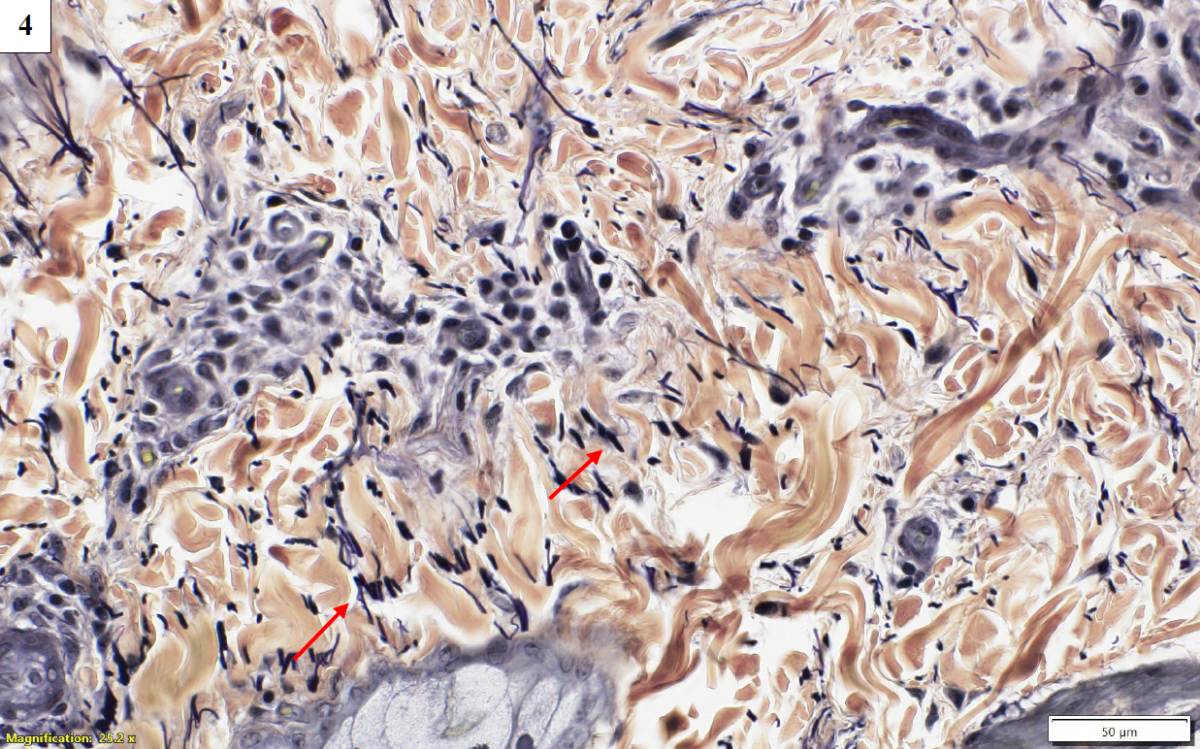

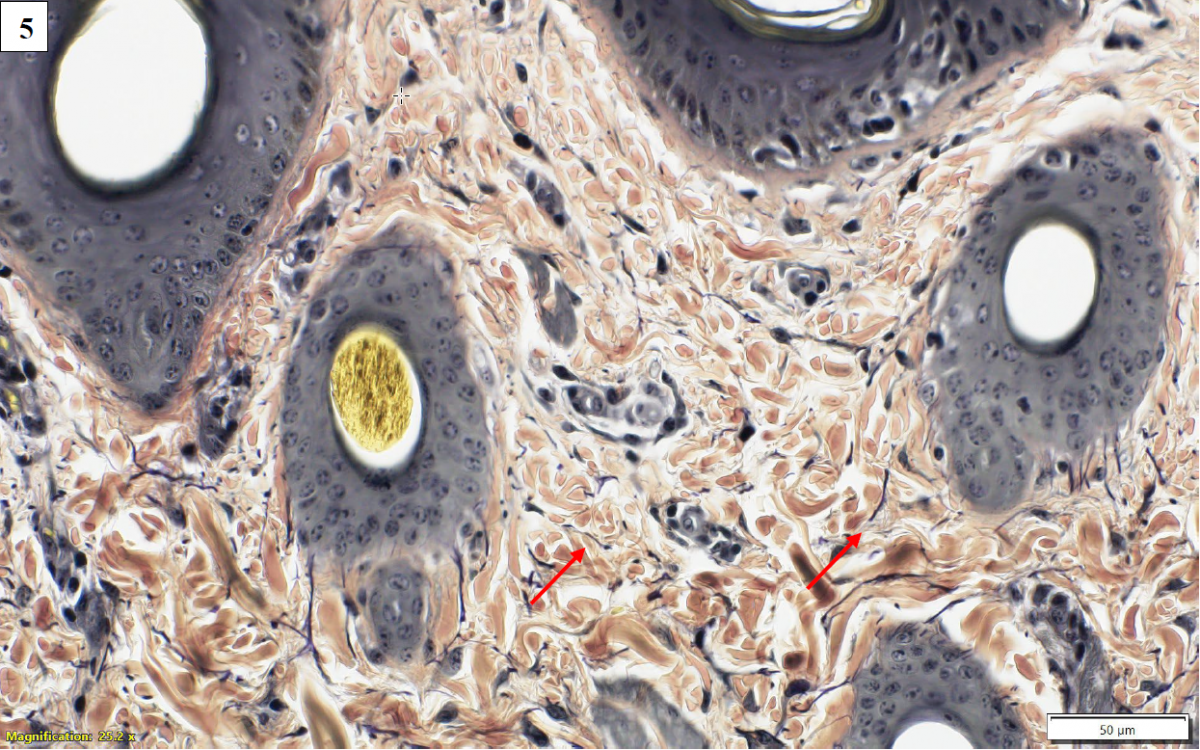

The age- and breed-matched control skin provided with the samples was determined to be histologically normal and was used as a control for a Verhoeff (elastin) stain. Comparing the two elastin-stained sections, it was noted that elastin fibres in the skin of the affected steer were mildly increased in number and appeared thickened, truncated, and haphazardly arranged (Fig. 4) relative to the control (Fig. 5). Based on these findings, a histologic diagnosis of collagen dysplasia was made.

Figures 4 and 5. Affected skin (top) and control skin (bottom), Verhoeff elastin stain, 40X magnification. Elastin fibres (red arrows) are increased in number, thickened, and truncated compared to control.

Further characterization of the collagen defect would require both ultrastructural examination (electron microscopy), and genetic testing. Electron microscopy was not pursued, and there is no commercially available genetic test for bovine dermatosparaxis. Since this animal was a feedlot steer and would not contribute to further herd genetics, additional confirmatory testing was not pursued.

Dermatosparaxis is an uncommon connective tissue disorder that is sporadically reported in cattle. Analogous to the human condition of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome type VII C, this condition is characterized by excessive loose folds of skin, skin hyperextensibility and fragility, slow or aberrant wound healing, and excessive bruising. The disorder is the result of a mutation in the gene for procollagen I N-proteinase which is the enzyme responsible for processing types I and II procollagen, resulting in accumulation of abnormal precursor molecules and inhibition of collagen cross-linking. Ultimately, this condition culminates in the inability to produce mature collagen.

In Belgian Blue cattle, dermatosparaxis has been associated with a deletion or substitution resulting in a premature stop codon in the ADAMTS2 gene. Reports of this condition in other breeds of cattle, including Draksensberger cattle in South Africa, and Limousin calves in Ireland, have not identified this specific mutation. AHL

References

1. Carty CI, et al. Dermatosparaxis in two Limousin calves. Ir Vet J 2016;69:15.

2. Holm, DE, et al. The occurrence of dermatosparaxis in a commercial Draksensberger cattle herd in South Africa. J S Afr Vet Assoc 2008;79(1):19-24.

3. Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Chapter 6: Integumentary System. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 6th ed. Maxie, MG, ed. Elsevier, 2016; vol 1:542-544.