Suspected copper storage hepatopathy in littermate Dalmatians

Emily Brouwer, Siobhan O’Sullivan

Animal Health Laboratory, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON

AHL Newsletter 2022;26(1):21.

Two deceased Dalmatian dogs were submitted to the Animal Health Laboratory approximately one month apart for postmortem examination.

The first dog presented to an emergency clinic for lethargy, vomiting and icterus following ovariohysterectomy surgery one week prior. Leptospira testing was negative. Clinical pathology testing identified marked elevation in aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and bilirubin. Euthanasia was elected.

The second dog presented to the same emergency clinic with a 24-hour history of vomiting and progressive lethargy. The dog was poorly responsive, laterally recumbent and had a short seizure. Clinical pathology testing revealed hypoglycemia, markedly increased ALT levels (beyond the analyzer limit), and prolonged prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times. Leptospira testing was negative. During assessment and treatment, the patient arrested, did not respond to cardiopulmonary resuscitation and subsequently died.

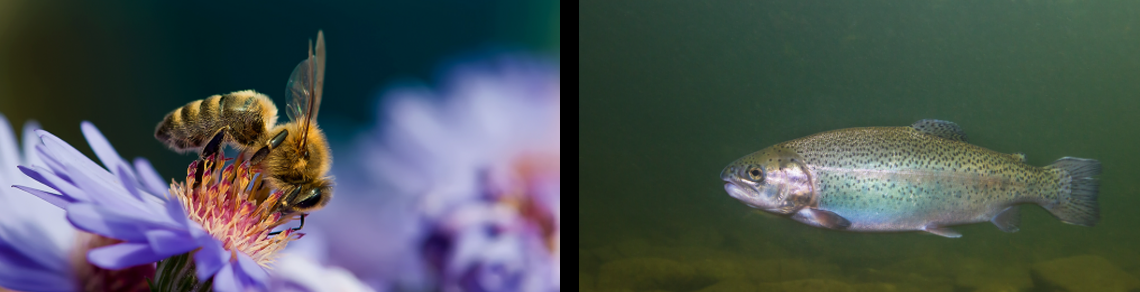

Postmortem examination identified marked icterus in both dogs, with subcutaneous petechiae in dog one, and extensive subcutaneous hemorrhage in areas of venipuncture for dog two. Both dogs had enlarged and discoloured brown/orange livers, with enhanced zonal patterns. Histologically, both livers had widespread acute midzonal to centrilobular hepatic necrosis with areas of panlobular necrosis. Special staining for copper identified widespread accumulation of fine granular pigment, consistent with copper, throughout all zones (Fig. 1). Quantitative copper levels were 1100 mg/g in both dogs, which is elevated from the reference range of 30-100 mg/g.

Figure 1. Widespread hepatocellular necrosis with hemorrhage (left, H&E stain); abnormal copper accumulation demonstrated by granular red pigment (right, rhodanine stain).

Following submission of the second dog, the emergency clinic communicated to pathologists at the Animal Health Laboratory that these animals were litter mates from separate households. Dog one had medication history (meloxicam) following routine spay, but no medication history was reported in the second dog. Toxicology testing (GC/MS) was requested for both dogs; results are pending. Given the breed, the similar clinical courses, and characteristic histologic lesions in combination with elevation of quantitative copper levels, the presumptive diagnosis for both dogs is copper storage hepatopathy.

Copper is an essential trace element that is required for various cellular functions. After absorption from the gastrointestinal tract, copper is transported to the liver where it is incorporated in enzymes or transported to extrahepatic tissues. Excess copper is typically secreted in the bile. In the event of abnormal accumulation or storage, excessive copper overwhelms lysosomal storage capacity and causes oxidative stress, free-radical formation and subsequent hepatocellular necrosis.

A specific genetic mutation that induces copper storage disease is well described in Bedlington terriers (COMMD1 deletion), and an underlying genetic cause has been proposed for other breeds including Labradors, Dalmatians, Dobermans and West Highland White terriers. Mutations in the ATP7B and ATP7A genes have been implicated in copper-mediated liver disease in Labrador retrievers, but the diagnostic utility in screening for these mutations is unknown, despite being commercially available. The genetic basis of disease in Dalmatians, while suspected, is not described.

Typically, definitive diagnosis of copper storage hepatopathy in dogs requires quantitative copper levels to exceed 2000 mg/g. In a retrospective study of 10 Dalmatians with presumptive copper storage disease, quantitative copper levels ranged from 754-8390 mg/g, with only 5/9 animals exceeding the 2000 mg/g threshold. In other types of copper-mediated associated liver injury such as chronic hepatitis, toxic levels of copper can vary, and an individual’s threshold for hepatic injury is likely multifactorial and mediated by factors specific to that individual, i.e., genetic, physiologic, and environmental factors.

The presumptive diagnosis of familial copper storage disease in these two dogs is based on characteristic clinicopathological derangements, gross and histologic lesions, and demonstration of abnormal copper accumulation using histochemical staining. While the copper levels were not as high as expected for a definitive diagnosis, examining these cases in parallel strongly supports the diagnosis in these two littermates raised in separate households. AHL

References

1. Webb CB, et al. Copper-associated liver disease in Dalmatians: A review of 10 dogs (1998-2001). J Vet Intern Med 2002; 16:665-668.

2. Webster CRL, et al. ACVIM consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic hepatitis in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2019 33:1173-1200.