SWINE

Mycoplasmal arthritis in swine

Josepha DeLay, Jim Fairles, Hugh Cai

Mycoplasma hyorhinis and M. hyosynoviae can contribute to infectious arthritis in swine. M. hyorhinis typically causes disease in pigs <10 weeks of age, and may lead to arthritis alone or, more commonly, in conjunction with polyserositis. In contrast, M. hyosynoviae usually causes lameness in pigs >10 weeks old, although there may be overlap in these clinical scenarios. Some practitioners have identified an increased prevalence of arthritis caused by Mycoplasma spp. in North American swine. This may, in part, reflect the increased sensitivity of new diagnostic tests using PCR techniques. Clinically, a diagnosis of mycoplasmal arthritis is often made on the basis of response to therapy. At the AHL, an average of 3 cases of mycoplasmal arthritis were confirmed annually from 2012 to 2016, most commonly M. hyosynoviae arthritis in feeder or finisher pigs.

Pigs are infected with M. hyorhinis and M. hyosynoviae from sows, or from infected herdmates at nursery age. Both may be commensal organisms, with localization of M. hyorhinis in the upper respiratory tract, and persistence of M. hyosynoviae in tonsil. Bacteremia precipitated by stress may lead to joint localization, arthritis, and clinical lameness. Any joint, and single or multiple joints, may be affected in an individual pig.

PCR is the method of choice for detection of both M. hyosynoviae and M. hyorhinis in joint fluid aspirates (preferred) or swabs. Presence of either organism in joints does not always lead to arthritis and because of this, PCR results must be correlated with histologic evidence of arthritis. Selection of appropriate pigs for postmortem exam and sampling is imperative in order to confirm mycoplasmal arthritis. Multiple (2-3) acutely affected, untreated animals should be identified clinically and euthanized for postmortem examination and sampling. Joints may not be obviously swollen in acutely affected animals, and clinical observation and identification of pigs that are reluctant to stand or overtly lame is very important in selecting optimal candidates for sampling. Chronically lame pigs, or pigs that are found dead, are not useful for diagnostic testing. In these circumstances, the primary pathogen responsible for infectious arthritis may have been eliminated and only secondary, opportunistic pathogens may be present.

Optimally, entire carcasses should be submitted to the diagnostic laboratory for evaluation of the cause of lameness. Many practitioners prefer to submit only multiple intact limbs from affected pigs for examination sampling, however more information may be gained if the entire body is examined. If on-farm sampling is undertaken, it is important to be organized and to maintain aseptic conditions for tissue collection. After removing skin over the joints, fluid from each joint should be aseptically aspirated and examined. Pigs with mycoplasmal arthritis usually have an increased amount of red-tinged, variably cloudy joint fluid. For each joint, the joint capsule should then be incised, and swabs taken from the synovial surface for bacterial culture. Multiple synovial samples are fixed in formalin for histologic examination, and an unfixed synovial sample is held frozen for additional PCR testing, if needed. Once opened, all joints should be examined for lesions of osteochondrosis (OCD), fractures, periarticular abscesses, or other conditions that may be contributing to lameness. Long bones should be examined grossly and histologically for evidence of metabolic bone disease. In lame animals that lack obvious joint lesions, examination of pelvis, vertebrae and spinal cord, and brain is necessary to rule out neurologic disease or bone lesions involving axial skeleton as the cause of lameness. AHL

Reference

Canning P. Diagnostic considerations for lameness. Ont Assoc Swine Vets Ann Mtg, King City, ON, 2016.

Summary of sample collection for diagnosis of infectious arthritis:

- joint fluid (1-2 mL, aspirated aseptically) in serum tube or other sterile container

- for Mycoplasma hyosynoviae and Mycoplasma hyorhinis PCR

- synovial swab (in transport medium, e.g., Culturette swab) – for bacterial culture

- several synovial tissue samples in formalin – for histopathology

- 1-2 fresh synovial tissue samples, in Whirl-Pak bag – to hold frozen for additional testing, if required

Parasitic pneumonia in finisher pigs

Josepha DeLay, Andrew Peregrine, Kevin Vilaca, Brent Jones

Two groups of finisher pigs developed severe, acute-onset dyspnea beginning 7-14 days following placement on straw in solid-floored barns; 70-90% of pigs in each group were affected. Parasitic pneumonia caused by larval Ascaris suum migration was suspected, based on housing conditions and on the large numbers of animals affected. The pigs were treated with injectable ivermectin (300 µg/kg subcutaneously), and most severely affected animals also received corticosteroids. Immediate and significant improvement was noted in most pigs in 1 herd, although a few (2-3) animals died. Death loss was significantly higher in the second herd, with 30% mortality, likely because of a delay in treatment. Lung and liver samples from 2 pigs in each group were submitted to the AHL for confirmation of the clinical diagnosis.

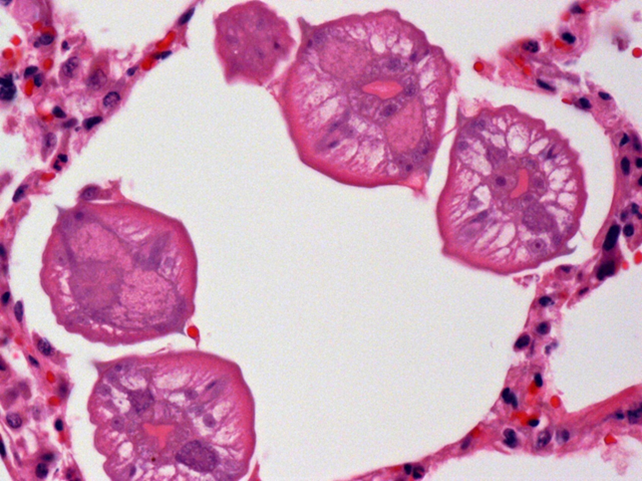

Grossly, lungs were firm and did not collapse. There was mild interlobular edema, and 1-2 cm diameter hemorrhagic foci were present multifocally in lung parenchyma. Histologically, aggregates of mixed inflammatory cells with prominent eosinophils filled alveoli and expanded interstitium, and surrounded bronchi and bronchioles. Variable numbers of nematode larvae were present in alveoli and in airway lumens, and were surrounded by hemorrhage and eosinophils. Small foci of necrosis and eosinophilic inflammation in the liver were variably associated with similar nematode larva. Streptococcus suis was isolated in large numbers from the lung of 1 pig, reflecting opportunistic infection secondary to larval nematode injury.

The severity of parasitic pneumonia in these pigs and the large number of affected animals likely reflect exposure to, and synchronous migration of, massive numbers of larvae in naive animals. Heavy environmental contamination was attributed to the flooring in the barns where these pigs were housed. Recent warm weather conditions in southwestern Ontario may have also contributed to an increase in survival of larvated eggs, resulting in a high environmental load of infective eggs.

Treatment with injectable ivermectin is necessary for rapid elimination of migrating L4 stages and resolution of clinical signs. In these herds, no additional deaths occurred after treatment, and the pigs gradually and completely recovered over 5-7 days. These cases serve as a reminder that A. suum is alive and well in Ontario, and of the importance of deworming and appropriate barn hygiene in preventing morbidity and mortalilty caused by this parasite. AHL

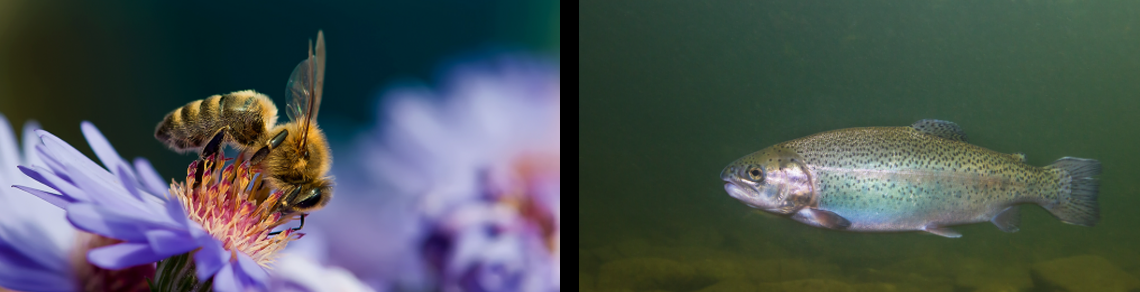

Figure 1. Lungs in situ from a pig with parasitic pneumonia caused by Ascaris suum. Note the multifocal hemorrhage and interlobular edema. (photo: Dr. K. Vilaca).

Figure 2. Several ascarid larvae in cross-section within a pulmonary alveolus.

Expanded anticoagulant rodenticide screen

Nick Schrier, Felipe Reggeti

The AHL is now offering an expanded anticoagulant rodenticide (AR) screen that covers 13 rodenticides; difethialone, flocoumafen, bromadiolone, brodifacoum, difenacoum, chlorophacinone, coumachlor (Fumarine), diphacinone, warfarin, coumafuryl, coumatetralyl, pindone, valone, and the natural occurring anticoagulant, dicoumarol. The method uses liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) instrumentation to achieve limits of detection in the low parts per billion (ppb) range.

Suitable samples include 10 g liver, 5 mL serum, 5 mL blood (red top), and 20 g of bait/source material. Specimens should be shipped frozen, with the exception of blood, which should be refrigerated in a sealed container.

The best diagnostic samples are liver and serum. The diagnosis of AR intoxication requires both the presence of one or more AR in appropriate samples (e.g., liver or serum) and antemortem or postmortem evidence of a coagulopathy unrelated to another identifiable cause of hemorrhage (e.g., trauma). Cost of the test is $90 per sample. AHL