Sector impact

Alliance-funded research aims to improve fish health and production for Ontario’s growing $98-million aquaculture industry by incorporating sustainable ingredients into fish feed.

![]()

Alliance-funded research aims to improve fish health and production for Ontario’s growing $98-million aquaculture industry by incorporating sustainable ingredients into fish feed.

Ontario fish farmers produce enough seafood every year to put more than 100 million meals on consumers’ plates, but it is not enough to keep up with the rising demand.

While the province’s aquaculture industry is well-positioned to grow, it needs to do so in a way that is ecologically and financially sustainable.

Dr. David Huyben, a researcher in U of G’s Department of Animal Biosciences, aims to bolster the growth and resilience of the Ontario aquaculture industry by helping farmers get the most out of their feed.

His research explores ways to replace costly feed ingredients with sustainable, lower-cost alternatives that meet the nutritional requirements of fish, improve their immune function and increase disease resistance.

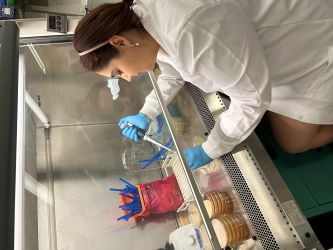

Undergraduate research assistant

Parnia Farsinejad assisted master’s

students investigating the effects

of insects and yeast on the growth

and performance of rainbow trout.

Huyben heard from Ontario producers that they were seeking functional ingredients—specifically insect meals—that meet the nutritional requirements and bolster the health of rainbow trout, the most-produced fish in Ontario aquaculture.

“Farmers have been requesting insects in feed, based on their own experiences,” he says. “We wanted to back that up with well-designed experiments into whether insect-based feeds help fish growth and health.”

In collaboration with Université Laval, the study aims to capture the impacts of insects and which component (protein, fat or fibre) improves fish growth, immune response and gut health. Results will support further provision of insect-based feeds for the industry while decreasing the environmental impact of fish feed.

“Insects are better for sustainability—to not sacrifice wild fish to produce an ingredient,” he explains. “We can’t use fish meal and oil to grow the industry. Insects are grown on waste substrates like wheat bran and rice hulls—agricultural by-products.

"There are also opportunities to reduce the carbon footprint of fish feed through local production and reduced transportation.”

M.Sc. Student Carmi Riesenbach

investigates protein, fat and fibre from

insect meal in diets for rainbow trout.

The researchers are also looking at the impact of dietary changes on fish gut microbes.

In the fish itself, the team is looking at amino acids and omega-3 fatty acids, which are important to health-conscious consumers seeking these essential fats and protein.

In additional trials, M.Sc. students Junyu Zhang and Cody Anderson are feeding yeast as prebiotics and probiotics to improve growth, nutrition and health of rainbow trout and zebrafish as a model species.

Results are expected in early 2025.

In a related study, Huyben’s team is responding to an increasing appetite for lake whitefish, a species native to the Great Lakes, while wild catches decrease due to climate change. Lake whitefish is valued by Indigenous communities, is high in omega-3 fatty acids and is increasingly in demand at fish markets across the province.

Huyben’s study aims to provide essential information to optimize diets for lake whitefish, which could lead to increased production and diversity of this species with high production and market potential in Ontario and across Canada.

A population of the fish is bred, maintained and studied at the Ontario Aquaculture Research Centre (OARC), which is owned by the Agricultural Research Institute of Ontario and managed by U of G through the Ontario Agri-Food Innovation Alliance.

As lake whitefish are new to commercial production, no specific diet is available for them. The lake whitefish at the research centre were experiencing inflamed bellies and sub-optimal growth. Huyben suspected these problems reflected a mismatch between whitefish physiology and the rainbow trout diets used to feed them.

M.Sc. student Rebecca Lawson nets a fish at the

Ontario Aquaculture Research Centre

Working closely with Ontario fish feed company Sharpe Farm Supplies, Huyben set out to determine whether the fish fared better on test diets with varying ratios of protein to fat. He and master’s student Rebecca Lawson also sequenced the gut microbiome—the collection of microbes in the gut—for the first time in a culture setting.

The team found that while fish grew better and were healthier on a high-fat, high-protein diet, the inflammation was likely due to sub-optimal genetics—something that needs further funding and research for this species to be established as a commonly farmed fish in Ontario.

“We’re finding out the gut microbiome not only produces fatty acids and vitamins, but it also interacts with the fish’s immune system, their brain chemistry and behaviour,” notes Huyben. “The fish gut microbiome needs more attention. A healthy gut would improve performance of the animal.”

The results of this study were shared with Sharpe Farm Supplies, which has used Huyben’s research to develop a customized feed for lake whitefish through its subsidiary Bluewater Feed. The commercial production and sale of this feed are expected in late 2024.

Huyben says that applying for Alliance funding to use research centre infrastructure owned by the ARIO helped push him to strengthen connections with industry.

“The Ontario Aquaculture Research Centre in Alma supports my work in many ways, from teaching to training, collaborations and research.”

Huyben was able to leverage Ontario Agri-Food Innovation Alliance funding for an NSERC Alliance grant, allowing him to fund five master’s students and increasing the potential impact of this work.

“In terms of aquaculture, U of G is number one and we have been a hub of research, training and information for the Ontario aquaculture industry since the establishment of the University’s Aquaculture Centre information hub in 1990.”

This research was funded by the Ontario Agri-Food Innovation Alliance, a collaboration between the Government of Ontario and the University of Guelph.